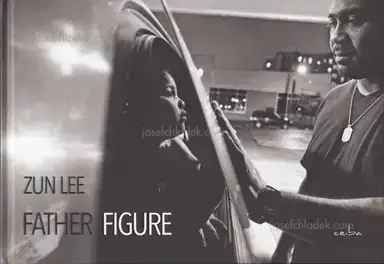

Zun Lee - Father Figure, ceiba, 2014, Lee

Zun Lee - Father Figure, josefchladek.com

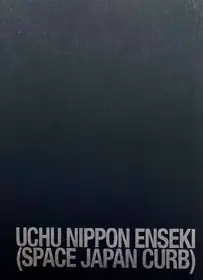

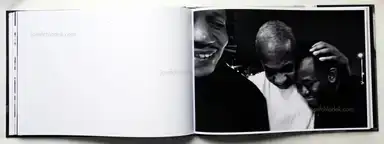

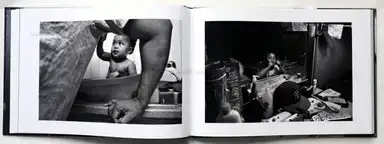

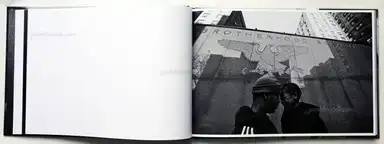

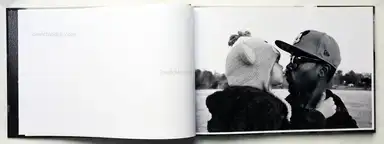

Sample page 1 for book "Lee, Zun – Zun Lee - Father Figure", josefchladek.com

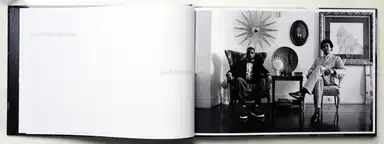

Sample page 2 for book "Lee, Zun – Zun Lee - Father Figure", josefchladek.com

Sample page 3 for book "Lee, Zun – Zun Lee - Father Figure", josefchladek.com

Sample page 4 for book "Lee, Zun – Zun Lee - Father Figure", josefchladek.com

Sample page 5 for book "Lee, Zun – Zun Lee - Father Figure", josefchladek.com

Sample page 6 for book "Lee, Zun – Zun Lee - Father Figure", josefchladek.com

Sample page 7 for book "Lee, Zun – Zun Lee - Father Figure", josefchladek.com

Sample page 8 for book "Lee, Zun – Zun Lee - Father Figure", josefchladek.com

Sample page 9 for book "Lee, Zun – Zun Lee - Father Figure", josefchladek.com

Sample page 10 for book "Lee, Zun – Zun Lee - Father Figure", josefchladek.com

Sample page 11 for book "Lee, Zun – Zun Lee - Father Figure", josefchladek.com

Sample page 12 for book "Lee, Zun – Zun Lee - Father Figure", josefchladek.com

Sample page 13 for book "Lee, Zun – Zun Lee - Father Figure", josefchladek.com

Sample page 14 for book "Lee, Zun – Zun Lee - Father Figure", josefchladek.com

Sample page 15 for book "Lee, Zun – Zun Lee - Father Figure", josefchladek.com

Sample page 16 for book "Lee, Zun – Zun Lee - Father Figure", josefchladek.com

Other books by ceiba (see all)

Other books tagged America (see all)

Other books tagged Father (see all)

Other books tagged Black & White (see all)

Hardcover, edition of 1000.

"Black father absence is a contentiously-debated social issue in the US and other countries. Too many Black men, so the argument goes, are missing, irresponsible, selfish, not stepping up to the plate. Visuals of deadbeat, absentee Black fathers abound in mainstream media, often intended to sensationalize and ridicule rather than to raise awareness.

These stereotypes did not emerge out of thin air. Married couples with children constitute less than one-fifth of African American households. Over 60 percent of African American children are raised by single mothers. As Americans are struggling to cope with the social and economic consequences of the worst recession since the Great Depression, it appears this will likely become more of a reality for not just Black children, but many kids of all racial groups.

Several complex factors play a part in this phenomenon, yet the numbers lead to the convenient assumption that many Black fathers are simply absent. Pundits across the political spectrum root this issue in a decline of morals and personal responsibility. If we encouraged a return to “traditional family values” and if only Black men would “stop acting like boys” and “pull themselves up by their bootstraps”, so the recommendations claim, we could reverse these trends and make our communities vibrant again.

The realities are not that simple. Studies show that individual circumstances are highly complex for many fathers, making the context of father “absence” and “presence” rather fluid: While many men may deserve the “deadbeat” label, many others simply do not fit traditional notions of fatherhood. Often forced to define parenting in their own specific ways, these men strive to be present despite adverse circumstances: They may not live at home with their partner or kids, they may not be legally married to their kids’ mothers and they may struggle to provide on a consistent basis, but this does not automatically mean that they are irresponsible. And I began to wonder why these examples of fatherhood remain so invisible when it comes to Black men. In fact, judging purely by popular media coverage, one could easily consider the term "Black fatherhood" an oxymoron.

It was not too long ago when a family secret was uncovered: My own biological father was a Black man who allegedly disappeared when he learned my mother was pregnant with me. For a long time, holding on to the pain of that discovery was easier than dealing with it: As long as I was able to project my misgivings onto a negative stereotype, I could justify my anger and hurt. But I also realized that a huge part of me was curious to know more about my Black father, wanting to understand, get to a place of forgiveness. And that longing had informed my creative process all along. Without any information about my father’s identity or whereabouts, the only way to come to terms with my feelings was to examine them through photography.

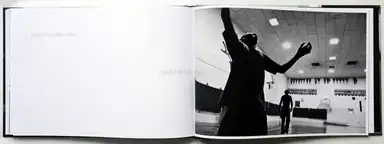

Over the past two and a half years, I’ve developed relationships with several Black fathers from different walks of life and in different cities in the US and Canada. Every father I met spoke with his own voice. They expressed their swagger, life rhythm, and ways of relating with their kids and partners in very unique ways. And perhaps more importantly, as I observed these families, another truth manifested loud and clear: Contrary to the prevalent media caricature of Black men as aggressive, violent, and irresponsible, the fathers I met were loving, affectionate, and dependable. They readily shared their feelings and emotions, their concerns and fears. They were vulnerable enough to allow me to photograph them in moments of joy and times of frustration. They were by no means perfect, but unsung everyday heroes nonetheless, committed to being present one fatherly act at a time.

Working directly with fathers was actually the last thing I would have wanted to do. Many of the encounters were filled with situations I had not experienced as a child, so they were difficult to witness, difficult to understand, and often difficult to photograph. But I knew I had to push past my resistance and spend time with these families – sometimes even live with them for a while. That was the only way to establish the level of connection necessary to make the images I wanted.

The work resulted in an ongoing project I dubbed Father Figure. By focusing on quiet moments that are deemed un-newsworthy, I hope this work can prompt people to question assumptions and become sensitive to the broader context of Black fatherhood. Perhaps it can also serve as a counterbalance to the prevalent visual narrative re. Black fathers.

In sharing of themselves so freely, the fathers I collaborated with gave me access to the richness of their human experience, which enabled me to find and share my own truth. That was perhaps the biggest gift I received and for that, I will always be grateful." (Zun Lee)

Pages: 124

Place: Verona

Year: 2014

Publisher: ceiba

Size: 31 × 21 cm (approx.)