Hans Danuser - In Vivo, Lars Müller Publishers, 1989, Danuser

Hans Danuser - In Vivo, josefchladek.com

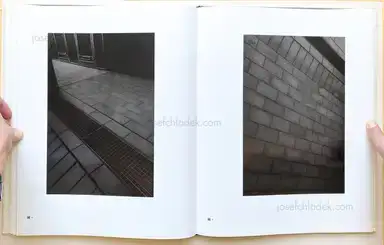

Sample page 1 for book "Danuser, Hans – Hans Danuser - In Vivo", josefchladek.com

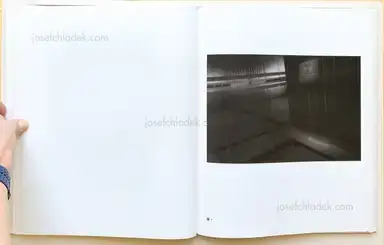

Sample page 2 for book "Danuser, Hans – Hans Danuser - In Vivo", josefchladek.com

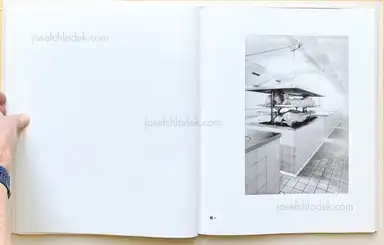

Sample page 3 for book "Danuser, Hans – Hans Danuser - In Vivo", josefchladek.com

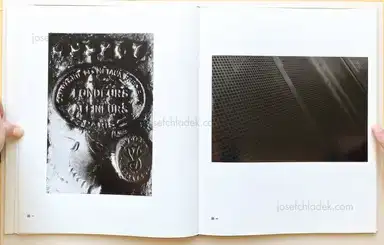

Sample page 4 for book "Danuser, Hans – Hans Danuser - In Vivo", josefchladek.com

Sample page 5 for book "Danuser, Hans – Hans Danuser - In Vivo", josefchladek.com

Sample page 6 for book "Danuser, Hans – Hans Danuser - In Vivo", josefchladek.com

Sample page 7 for book "Danuser, Hans – Hans Danuser - In Vivo", josefchladek.com

Sample page 8 for book "Danuser, Hans – Hans Danuser - In Vivo", josefchladek.com

Sample page 9 for book "Danuser, Hans – Hans Danuser - In Vivo", josefchladek.com

Sample page 10 for book "Danuser, Hans – Hans Danuser - In Vivo", josefchladek.com

Sample page 11 for book "Danuser, Hans – Hans Danuser - In Vivo", josefchladek.com

Sample page 12 for book "Danuser, Hans – Hans Danuser - In Vivo", josefchladek.com

Sample page 13 for book "Danuser, Hans – Hans Danuser - In Vivo", josefchladek.com

Sample page 14 for book "Danuser, Hans – Hans Danuser - In Vivo", josefchladek.com

Sample page 15 for book "Danuser, Hans – Hans Danuser - In Vivo", josefchladek.com

Sample page 16 for book "Danuser, Hans – Hans Danuser - In Vivo", josefchladek.com

Sample page 17 for book "Danuser, Hans – Hans Danuser - In Vivo", josefchladek.com

Sample page 18 for book "Danuser, Hans – Hans Danuser - In Vivo", josefchladek.com

Sample page 19 for book "Danuser, Hans – Hans Danuser - In Vivo", josefchladek.com

Sample page 20 for book "Danuser, Hans – Hans Danuser - In Vivo", josefchladek.com

Sample page 21 for book "Danuser, Hans – Hans Danuser - In Vivo", josefchladek.com

Sample page 22 for book "Danuser, Hans – Hans Danuser - In Vivo", josefchladek.com

Other books by Lars Müller Publishers (see all)

Other books tagged Black & White (see all)

Other books tagged Nuclear plants (see all)

Other books tagged Science (see all)

Hardcover with dust jacket.

"Aufgenommen in den USA und EUROPA, 1980 – 1989"

I: A-Energie, II: Feingold, III: Medzin I; IV: Los Alamos; V: Medizin II; VI: Chemie I; VII: Chemie II.

Research is inseparable from the concept of the new or of the implicit that has not yet been made explicit. Research unearthing the known and familiar would be a contradiction in terms. The new, in turn, is closely related to the taboo. Wherever the truly new is being explored, con- troversies almost inevitably ignite—not only of a scholarly, but also above all of an ethical and moral nature. When Hans Danuser was working on his cycle In Vivo (1980–89), as a photographer scouting out the inner lives of nuclear power plants and chemistry laboratories, he touched on such taboos. Nuclear energy, genetic research, and the chemical industry, along with the usually unspoken-of areas of pathology and anatomy, are phenomena that most of his contemporaries knew only from the consumer side: electricity, medicines, therapies.

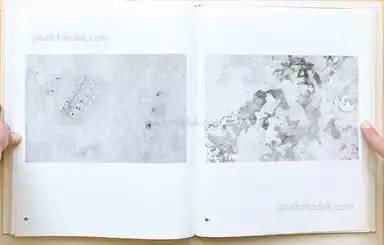

Danuser did not just call attention to these highly inaccessible yet omnipresent areas of mod- ern societies. Newspaper articles or television reporting could do a better job of that. Danuser presented the indexically grounded (through analog photography) and subjectively interpreted atmospheres of these places, and offered new perspectives on them. Even more than that—or, more precisely, even less than that—his photographs show that some things cannot be shown, that something cannot be represented in the representation, that the photographs always con- ceal as well as reveal. As Urs Stahel wrote of In Vivo in 1989, it is striking “that in several [...] pho- tographs one hardly sees anything at all,” that Danuser “fades the so-called factual into the white” or allows it “to sink into the black.”3 Negation hardly ever plays a role in traditional documentaries or reportages. Danuser, by contrast, produces images that call themselves into question. But not only themselves.

Looking at the photographs of In Vivo, it is almost impossible to understand oneself as a sovereign subject that exercises control and mastery over that which it has created or that which was created by others. This is by no means a self-evident realization. Pictures, especially those created using single-point perspective, play an important role in the secular story of the self- empowerment of humanity, according to Martin Heidegger: “The fundamental event of modernity is the conquest of the world as picture. From now on the word ‘picture’ means: the collective image of representing production [...] the unlimited process of calculation, planning, and breed- ing.”4 Danuser’s photographs can be understood as a critique of such pictorial practices. Where- as, on the one hand, he opens up difficult-to-access spaces to the public eye, on the other hand, in his photographs he closes off the proverbial unlimited possibilities and the expansion of areas of control that people in the secular West have expected of the new since the beginning of the modern era. In his photographs, the supposed overcoming of taboos never completely emerges from the shadow of the taboo. Whether it is the production of gold, laser research, or tempo- rary storage of nuclear waste, the photographs of In Vivo are dominated by the un-thought, the unavailable, the imponderable. (Jörg Scheller)

Pages: 120

Place: Baden

Year: 1989

Publisher: Lars Müller Publishers

Size: 30 × 38 cm (approx.)